Sustainably foraging teas on Whidbey all year

I'm taking part in a 10-minute skill share gathering tonight at the Koneski Co-Creative Gallery in Clinton (5:30 to 6:30 pm if you care to join us). This is the content of the handouts I'm taking. I'm also planning to host classes on this subject in 2026: likely one class for each season. Until then, I have this to share...

Becoming an ethical forager means that you are coming into close relationship with everyone and everything around you. It’s a lifelong practice of delighting in and awakening to deeper connections, of grounding in the place you live, and of decentering humanity for a while (learning with and from local animals, insects, plants, land, waterways, weather patterns, etc.) and then returning to humanity to offer what you find/learn/forage. To me, it means being a good ancestor.

Foraging is a tradition that spans all human backgrounds. You have foragers in your lineage. You have foraging skills in your DNA. You can do this.

Ethical foraging tips from me and my people and teachers

Off the top of my head, I came up with 11 tips. We may be lovely, but we aren't exactly brief. ;-) Tips from my people:

- Relationships first. Get to know the plants, land, trees, weeds, wildlife, insects, the community, and land stewards/owners before you forage & as you forage. If you value enthusiastic consent within healthy human relationships, then you already know the most important part about moving through the world as an ethical forager.

- Forage at home & close to home where you already walk regularly first, then outward, in larger circles, as you become trusted by others (land, plants, insects, wildlife, people, and waterways) and as you trust yourself more and more. As you begin, gather from where you go naturally and often—where you know the land best. Where you’ll naturally introduce yourself to neighbors and build relationships. Cultivate friendships with places, plants, birds, gardeners, farmers, foragers, deer, squirrels, and other land tenders/lovers/stewards/owners. Foraging in backyards, fields, at neighbor’s houses, on farms, etc. is foraging. I gather from our friends’ & neighbors’ yards, places where we walk our dog regularly, on our own small piece of land, and with some farmer and herbalist friends on land they love/tend/share.

- Find & move with the generosity at your core. Nature is generous by, um, nature. So are you. Generosity rises from awareness of interconnectedness and feeling well supported: both felt from within. Cultivate an awareness of what generosity within you feels like in your body. As you’re moving through the world, when you notice that feeling of generosity within you, stop, take a deep breath, and look around. There may be a stand of plants, a weed, a tree or forest, a river, a field, a squirrel, a bird, a park, or a person in the mood to show you something or share with you.

- Be a good neighbor: gather only from abundance. Leave most for wildlife and other neighbors. What is most? If you visit often and know the land & stand of plants really well, then you’ll know what abundance looks like, what healthy forests/fields/plants near you look like, and how much is enough and too much to take. Until then, ask people who know the land, stand, tree, waterway, or plants better than you or talk to experienced local foragers, herbalists, land-loving farmers, indigenous folks, avid gardeners, and old people who’ve been in the area a long, long time (or others deeply connected to the land). Don’t gather endangered, over-harvested, or stressed/sick plants. If you really want them, go elsewhere or try cultivating them at home, friends’ homes, or in community gardens. Harvest from abundance.

- Foraging without gifting isn’t as fun or sustainable. What you gather when foraging is a gift. To increase joy, offer gifts back when possible. Gift ideas… Share a song, a poem, another plant or flower, a story, something you made with friends, or share how you will use what you take and who you’ll share it with. Bring/offer water during dry seasons. Ask a stand, tree, forest, or field if they’d like to be your friend & commit to listening there more (some herbalists call this finding a plant ally or land ally). When you can, gift every time you forage—to at least one being you’re in relationship with: the plant, the stand of plants, the field, the forest, the land stewards, or someone who can’t forage or access land. Thank ancestors and neighbors who cultivate(d) or protected the plant/tree/land. Exceptions: 1) If you befriend/ gently tend the stand regularly and know it well, your full presence together may become gift enough. 2) If you’re lost and when you really hungry/thirsty, or emotionally drained, unsheltered, or feel like you have nothing to offer the world, then your gift is to receive and refill. Period. Being fully present & aware you need help—and are receiving help from the green world around you—is your gift. Fully present, open, and listening humans are a HUGE gift.

- Be a really good neighbor as community: Regularly visit and learn to care about stands of plants and land. Visit in each season to see what changes. Learn from all beings present. Do you know what the frogs there say and do? The birds? Have you listened to the stand of wild roses? To Doug fir trees? To sun and rain there? Listen and watch out for them like adult and elder friends. Speak up for them. Learn to talk about weeds, plants, trees, and land you love like they’re beloved family. Are there plants not thriving this year? Why? Gather/scatter their seeds as you move through the world. Share about stand locations sparingly: only with people in dire need and if you are tending and expanding the stand or the plants in the stand elsewhere. If you are tending and expanding the stand, then you can share with a few people you trust or teach to be sustainable foragers. Or, wait to share the stand location until you believe you’ve met the next person who will tend the stand or someone willing to tend the stand/land with you.

- Notice the conditions, neighbors, and locations that wild plants choose for themselves. Learn more than you help (99% learning, 1% helping) most days. Gather/spread seeds like birds, squirrels, and other animals do, for example. When wild stands are threatened and you can’t help them where they are, think about contributing to starting new stands in similar conditions elsewhere. How much permission you need to do this depends on you: how safe and welcome you feel in the world and how safe and welcome you make others feel. Wild fields, forests, and plants are fierce, connected, wily, and wise. Most prefer either no human help or only the tiniest bit of help. I once got really angry when the county accidentally mowed down an entire new stand of Nootka roses I had started & was using for my herbalist practice. As it turned out, I should have waited before getting angry. Mowing them caused them to spread twice as fast and far as before! The roses knew. I didn’t. Me talking to the county meant they’ll avoid mowing down the growing stand going forward, because, I learned, they love Nootkas too, for different reasons.

- Life is life. Offer the same respect and courtesy to all life that you do to other humans (or vice versa, if you’re great with forests and plants but not great with humans). One way to forage in winter is to host a tea swap with human neighbors. Have everyone bring extra packaged and foraged teas and then swap to expand the diversity of what everyone has. Think about how you would treat people who show up to this event. How happy you are to swap. How grateful you are that they’re present and willing to share from their abundance and contribute to yours. That’s how you should be feeling—most of the time—when you’re moving in the world and when foraging. The forest, the plants, the weeds, the wildlife, the insects, and the land should be able to feel that gratitude-for-their-presence within you. You can start with that gratitude and spread it as you move. Or, you can go into the yard, neighborhood, field, or forest aware that the beings there will help you remember that gratitude. And then, be grateful for that.

- In the U.S. and many other places, access to land is a social justice issue. If you care about social justice, you’re never just building relationships with land, trees, plants, and land stewards/owners for yourself and your family. You’re building those relationships to lean on them and share them with those who who’ve been denied access to the land, don’t have access today, had land stolen, or who cannot access local land as safely as you can. If you think the land and forests don’t care about these issues, that’s fine. Consider doing your foraging only on your own land and close neighbor’s lands. Leave dwindling public lands for those who deeply need them.

- Avoid taking slow-growing beings (like usnea lichen) from trees or cutting long-living trees (such as conifers) until you hear clear, joyful permission—enthusiastic consent, born from connection and abundance—from the land, the trees/lichen themselves, and the best human land stewards of the region or teachers that you can find locally. It took me more than 7 years here on Whidbey to receive those permissions, and I still prefer to gather usnea and conifer branches only from the ground after windstorms. I take fir tips only from abundant places and where trees are growing into each other or onto paths or roofs. I almost never have to cut trees. Exceptions: 1) if you need shelter/sustenance to survive & no humans are present to help, take what you need. The forest absolutely wants to help those in dire need. 2) if community/family members have cut branches to protect/expand structures, roads, or paths, put cut branches to good use. Don’t waste them. Become known as someone who accepts branches that had to be cut. Make friends with others doing the same. Share.

- Don’t interrupt joy and playfulness. If you see children laughing/dancing/picking every dandelion flower in the field (when you were taught that’s not right), stop yourself before you interrupt. That dancing and joy may be exactly what that field or tree roots most want and it’s likely exactly what the children—and maybe you—need too. Celebrate joy. Apprentice yourself to playfulness wherever it shows up. Don’t assume you know better just because wise adults said you should only take every 7th dandelion flower. Most wise adults have much to learn about what the plants/trees/land in any give place truly need. Stay in the moment, grow quiet, and listen a long time before you interrupt joy. Feel playfulness or joy first. Before you interrupt them. That’s what playful elders do.

Special tips for people brand new to foraging

If you're brand new to foraging:

- You can do this. I promise.

- Foraging where you typically walk is a fantastic way to start. Almost every “weed” is either food, tea, medicine, or a life lesson in waiting. When you respect everything growing near/beneath your feet, then it’s time to move outward to forage in a larger circle.

- You can forage without taking plants/plant parts as you learn. For example, you can just introduce yourself. Observe. Listen. Sit and relax. You can ask and listen for answers to any question. You can show up and ask what the place most needs. You can grieve knowing that you are completely surrounded by fully present, non-judgmental beings. You can dance. Tree roots love dancing. You can bring a journal, sketch pad, or art supplies and write, sketch, or create art. Drawing plants, trees, and their surroundings and neighbors is an excellent way to get to know them. And typically far less awkward than with humans. And prepares you for teaching, which you may find yourself wanting to do some day.

- When foraging for plants to consume, be 100% certain that you’re foraging the correct plant. If you’re not 100% certain, don’t take the plant. Leave it be. Sketch it or take a photo. When foraging for plants to consume you must know the plant as well as you know your other dearest friends' faces, habits, and preferred locations and friends. Know what the plant—and any plant parts you forage—smell like. Knowing the smell of a plant can save your life. You could also return with a human being who knows the plant really well, or ask an elder who knows the land and has history with the plant, or simply move on to other plants you know well, take a class, read a book, and try again next year. In-person classes are best because you have to learn what things smell like and look like in different seasons. My own philosophy is that if the human teacher doesn’t stretch me a bit, help me trust myself and others a little more each day, ask us to use multiple senses, and take responsibility for their own emotions and their impacts, then I move on to another teacher. (That’s what I need as a sensitive, empathic being. What you need may be different. The important part is to understand what you need in a teacher and take action sooner rather than later to get it.) Plant apps are great! And, they can only tell you what the plant is likely to be. They don’t offer what conditions the plant likes, what neighbors tend to be around them where you live, what the plant and its parts smell like and look like in different seasons, or what this particular land or stand of plants might need of a new human friend. “Likely” isn’t good enough when foraging for what you and your friends and family will consume.

- New, enthusiastic foragers often naturally gather too much for themselves. That’s ok. Preserve the extra & plan to share it with people who forage elsewhere/have different plants than you, at swap and barter events, in Buy Nothing groups, and with people who cannot forage for whatever reason. You can also gift dried plants back to other plants, trees, & land as thank yous. In time you’ll learn how much is enough. That’s one of the deepest gifts of foraging.

- If you insist on foraging alone in the wilderness for green plants/leaves/stems/roots that are new to you, consider starting your foraging journey in the summer or returning to the same place regularly and watching for an entire year before you forage. This is only for newbies. Typically, we forage when the plant is ready or the part of the plant we want is at its peak (blossoms generally in spring, fruits generally in the summer, roots generally in the fall, etc.) or when we need the plant. But, if we’re new to foraging and we insist on foraging alone for plants that are new to us, then this tip makes sense. As plants emerge in the spring here, many look similar in their emerging and youngest stages. And their scent may not be as strong or distinguishable from all the other scents of spring. By mid-summer, many plants are in their full form and their scents and other characteristics are distinguishable. An example of this is burdock: a gorgeous medicinal, tea, and food plant with many lovely qualities. In its first year, as it first emerges from the ground in spring, it can look like foxglove, which is also emerging from the ground at the same time. Foxglove, if mistaken for burdock, can kill you or make you very sick if you digest it. By summer and into the fall, burdock looks and smells nothing at all like foxglove. The same goes for the poison hemlock around here and its “look-alike” plants such as cow parsley and queen anne’s lace. All the obvious differences show up as the plants mature. If you’re not 100% sure that you’re standing before a dear friend, don’t take and consume the plant.

Seasonal foraging for tea on Whidbey (our family’s favorites*)

We are lucky to be here. There are many plants that can be used for tea, in abundance, here: many wild, many cultivated, many weedy, and also a few tasty and useful plants (I don't call them invasives) that aren't great neighbors to native plants who have been disturbed, disrespected, and harmed by humans not deeply connected to the land, for generations.

In the springtime (use fresh, ideally, or preserve for later use): Douglas fir tips (typically May or early June is best), spring-growth stinging nettles, Rose petals, Hawthorne flower/early leaf (typically May), Cultivated mints, Chickweed, Purple dead nettle, Cleavers weed (cold infusion best), Comfrey leaf and flower (typically May & June, harvest only when flowering and only from purple-flowered varieties), Apple, plum, cherry, & crab apple blossom (from ornamental varieties or selectively from trees that over-produce fruit), Plantain leaf (late spring) Elderflower (take only a few and only from large plants—stick with flowers from black/blue elderberry plants only), and Horsetail (harvest tops spring and very early summer only while spindles are pointing up. When pointing down they may have too much silica for tea making)

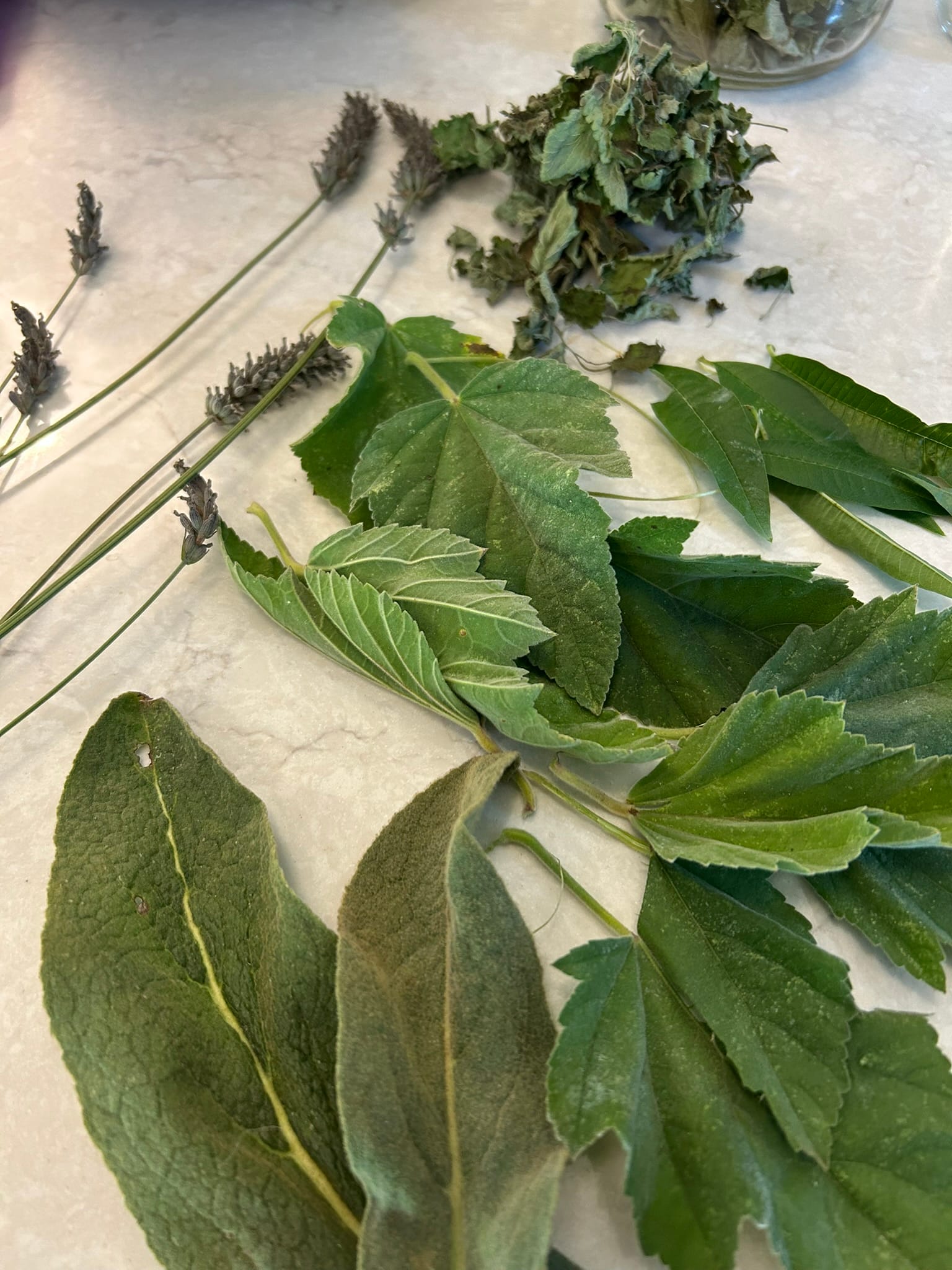

In the summer (use fresh and preserve for use year round): Comfrey leaf and flower (early summer), Red clover (clover and surrounding new petals/tops), Rose petals, Peppermint, Spearmint, Catmint, Calendula petals, Lemon balm, Lavendar, Lemon verbena, Plantain leaf, Fireweed (July-August when flowering), Goldenrod (late summer/early fall when flowering—flowering tops look like feathers, don’t confuse with tansy ragwort or st. john’s wort which also bloom yellow), Stinging nettle seeds, Elderberries (black/blue, not red) (late summer and early fall), Tulsi/holy basil, dock seed (better infused in vinegar than as tea), marshmallow leaves (ideally before flowering), Mugwort (ideally before going to seed), Oatstraw (whole plant, above-ground parts) if you’re old-school or milky oats (tops captured at the milky stage) if you enjoy trends, Black huckleberries, Blackberries, Salal berries, corn silk and husks

In the autumn (use fresh and preserve for use year round): Autumn-growth stinging nettles (young/new plants emerge in the fall again—don’t use the old plants), Rose hips, Dandelion root, Hawthorne berries, all the mints, lemon balm, lemon verbena, pineapple sage (and other fruity sages), Calendula petals, fruits (e.g., apple, plum, peach, quince, pear), Black huckleberries, aster flowers, Ginkgo leaves, marshmallow root, dock root, and burdock root (Be 💯 certain on this ID—safest to harvest in the fall when the plant is very clearly not foxglove)

In the winter:

Forage outside for crab apples, small rose hips (Many smaller hips last into winter while larger Rugosa hips tend to get soggy by start of winter here.), rosemary, and windfall branches & buds. We gather these off the ground after fall and winter windstorms: 1) Douglas fir (lemony pine-y flavor), 2) Grand fir (orange pine-y flavor), and 3) Pine branches. Strip needles off windfall branches and use needles for tea. Also, cottonwood buds (infuse into honey and use the amber-y sweet honey in/as tea—too bitter straight into water) and western red cedar sprays (useful as a foot soak bath or steam inhalation—we don’t drink this one).

Forage inside:

- Forage your own shelves. Use and share everything you gathered and preserved in warmer months.

- Make a wintertime tea blend: mix a few of your simples (one plant in one container or menstruum) together. If you have extra, this makes a nice gift!

- Experiment with adding a dash of traditional culinary warming spices from the cupboard (cinnamon, allspice, nutmeg, star anise, cloves, pumpkin pie spice, black pepper, etc.) into warm teas and milks.

- Use your infused honeys. We infuse rose petals, lilac flowers, honeysuckle flowers, and other tasty or medicinal plants into honey in summer and fall and then use the honey with tea, or as tea, all winter.

- Use home canned juices and tonics in/as tea. I make and can an elderberry tonic in early autumn, for example. In winter, I gently warm it, stir in honey, and then we have elderberry syrup whenever we want it.

- Some plants do well in the freezer. We steam and freeze some stinging nettles for winter. We chop cleavers weed into ice cube trays, fill with water, and freeze. Then drop into water/juice and drink (good for winter-stagnant lymph).

Winter is a great time to gather and grow closer to your human community while leaning on your green community:

- Swap packaged and foraged dried teas. Host a swap party—sharing and drinking a wide range of plants is fantastic for community and for our gut biomes. Leaning on the 1) South End Exchange, and/or 2) Whidbey Homemaker Bartering, and/or 3) Whidbey Island Trade and Barter groups on Facebook and/or on Koneksi gallery hosting would be great ways to do this.

- Ask for/give teas in the Buy Nothing Whidbey Island (South) or Buy Nothing Whidbey Island (North) Facebook groups.

- Reach out to herbalists who gather locally. We have dried plants on hand and almost always too much of something. Some sell plants for teas/infusions (a favorite: Nourishing Herbal Infusions | Crow's Daughter). Many of us happily gift our extras.

- The Goose’s bulk herbs section is lovely—find employees or nearby shoppers who are herb lovers and ask about their favorites for tea in the winter. Wintertime is also an excellent time to try a tea from another land. See what local stores or food pantries offer. Try something from somewhere sunny to help get through our darkest days.

Almost year round on Whidbey: Blackberry leaf, rosemary, mints (We grow mints in whiskey barrels on the shady, north side of our house that emerge as early as February and that last as late as December some years), weather-hardy and frost-protected herbs such as sage, thyme, marjoram (ours last all year or almost all year), Douglas fir, Grand fir, & Pine branches can be gathered off the ground year-round and the needles used for tea. They’re best gathered after fall and winter windstorms. Fir tips—which many people think make the best tea—are best gathered as they emerge in the late spring/early summer. Good fresh or dried.

Also, citrus peels destined for the trash can, immersed in honey for a while instead, make great honey/tea. A fancy version is to put a few slices of meyer lemon or orange, fresh ginger and turmeric, and a few whole black peppercorns in a jar, fill it with honey, and invert it daily for a couple of days until the honey is runny. Then store it in the fridge (setting the jar in a bowl) and use spoonfuls to stir into tea or into hot water as a tea. I think this was originally seed-saver Rowen White’s recipe.

During times when you don’t have money to spend or capacity/ability to forage outside, visit our local food banks/pantries to forage for teas. Good Cheer (Langley/Bayview), Queen Bee Pantry (Greenbank), Gifts from the Heart (Coupeville), North Whidbey Help House and Garage of Blessings (Oak Harbor).

During times when you have extra teas/tea plants, join or make friends with people running one of our many local soup kitchens and share your extras with friends there: Whidbey Island Nourishes (Langley), Open Tables Soup Kitchen (Langley), Island Senior Resources (Langley, Oak Harbor, and Camano), Spin Café (Oak Harbor), St. Huberts (Langley), Island Church (Langley), or share with Whidbey Homeless Coalition (The Haven near Coupeville & House of Hope in Langley) or Ryan’s House near Coupeville.

* Many of these loved-by-our-family plants have health/wellness/medicinal uses far beyond just making a tasty, refreshing, or soothing cup of tea. It's important to know both the plant and yourself well. If you have a chronic illness, allergies, or condition, are pregnant/breastfeeding, are taking pharmaceutical medications, or are worried about trying a new plant as tea for any reason, consider checking with someone who understands the ramifications of adding new-to-you plants, such as your own intuition and understanding of yourself, an elder family member who knows deep family history, a clinical herbalist, a naturopath, a nurse practitioner, a doctor, and/or a wellness team of folks. Healthy people and herbalists have used these plants as teas for generations, which is how we know they're generally safe. But it's still important to know how to respect them, gather and preserve various plants and parts, steep times, what to avoid when working with them, tea making methods for various plants and plant parts, and how plants are likely to interact with you, specifically.

A few tea- and tea-adjacent terms from the herbalist world

tea –steeping fresh or dried leaves, stems, petals, flowers, berries, or fruits, for a short period of time, typically 1 – 5 minutes or up to 10 minutes. Made by pouring hot or boiling water over the plant. Best for tasty or super fragrant plants whose flavor & essential oils contribute to wellbeing but degrade with prolonged exposure to water. Some plants may be steeped longer if being taken medicinally. Lemon balm, for example, is tasty steeped for 3 minutes and far less tasty if steeped for 20 minutes, but its relaxing impact on your system may be better when steeped for 20 minutes, depending on your issue.

infusion – a long-steeped nutritional tea-like offering that supports overall wellness, typically steeped 4 to 8 hours or overnight, typically made by pouring boiling water over nutritious plants (for example, stinging nettles, linden, oat straw, red clover, comfrey, hawthorn flowers/leaves) or sometimes by infusing a plant in cold water for a long period of time (cleavers weed, marshmallow leaf or root infuse well in cold water). Many herbalists drink 2-4 cups of herbal infusion per day for overall health.

decoction – for plant parts that are hard/thick, such as some roots, dried roots, dried berries, and bark – put the plant into a pan of water on the stove, bring the water to a boil, and allow the plant to simmer/soften into the water, typically 20-30 minutes. While you might make a tea or infusion of hawthorn flowers or leaves, to get the most out of the dried berries, you'd choose a decoction.

bath or foot bath – for plants gentle, powerful, and pleasing enough to immerse your feet, or whole body, into. Made by adding plants to hot water or milk and immersing your feet or whole body into them. Can also be for plants considered too strong to take internally, or best topically received (or received via steam too), and plants that are helpful for the nervous system but not palatable to consume, for example, some people don’t like the taste of lavender as tea but will happily take a lavender bath

steam – put plants into a pan of water, bring to a boil, lower to a simmer to avoid splashing/burns, and then hold your head above the pan to inhale the steam. Another way to get plants into your system using water.

honey – Honey is a great menstruum for plants, buds, and roots that don’t taste good as plain tea: cottonwood buds, elecampane roots, and garlic are examples of this. Honey is also a great preservative for flowers that taste best or different fresh, such as rose petals, lilac flowers (no green parts), and honeysuckle flowers. Honey has healing properties of its own and is easily stirred into other teas or made into a new tea by infusing plants into it. Its sweetness also makes it easier for many people & kids to enjoy more plants.

broth – some plants and fungus are really good for you but don't taste good (to most people) as plain tea. Onions, garlic, sage, chives, oregano, thyme, and mushrooms are good examples. Instead of trying to make tea from them, add them to a warm vegetable broth or meat broth/stock and then sip the broth as you would drink tea. Especially good in cold fall and winter months, exactly when you need them. Almost as if the plants we need appear in the season we need them (that's a whole other class). If family won’t drink broth, make the broth into soup or stew. Whatever works. 😊